If New Metal Legs Let You Run 20 Miles/Hour, Would You Amputate Your Own?

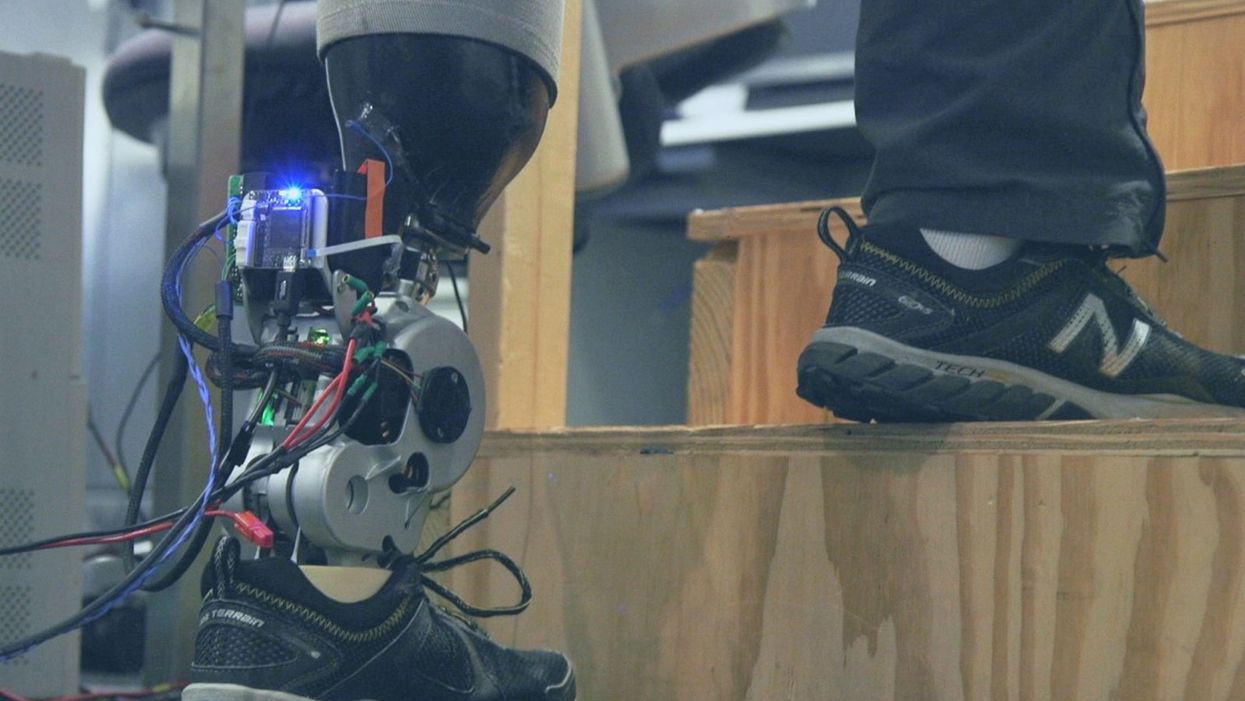

A patient with below-knee AMI amputation walks up the stairs.

"Here's a question for you," I say to our dinner guests, dodging a knowing glance from my wife. "Imagine a future in which you could surgically replace your legs with robotic substitutes that had all the functionality and sensation of their biological counterparts. Let's say these new legs would allow you to run all day at 20 miles per hour without getting tired. Would you have the surgery?"

Why are we so married to the arbitrary distinction between rehabilitating and augmenting?

Like most people I pose this question to, our guests respond with some variation on the theme of "no way"; the idea of undergoing a surgical procedure with the sole purpose of augmenting performance beyond traditional human limits borders on the unthinkable.

"Would your answer change if you had arthritis in your knees?" This is where things get interesting. People think differently about intervention when injury or illness is involved. The idea of a major surgery becomes more tractable to us in the setting of rehabilitation.

Consider the simplistic example of human walking speed. The average human walks at a baseline three miles per hour. If someone is only able to walk at one mile per hour, we do everything we can to increase their walking ability. However, to take a person who is already able to walk at three miles per hour and surgically alter their body so that they can walk twice as fast seems, to us, unreasonable.

What fascinates me about this is that the three-mile-per-hour baseline is set by arbitrary limitations of the healthy human body. If we ignore this reference point altogether, and consider that each case simply offers an improvement in walking ability, the line between augmentation and rehabilitation all but disappears. Why, then, are we so married to this arbitrary distinction between rehabilitating and augmenting? What makes us hold so tightly to baseline human function?

Where We Stand Now

As the functionality of advanced prosthetic devices continues to increase at an astounding rate, questions like these are becoming more relevant. Experimental prostheses, intended for the rehabilitation of people with amputation, are now able to replicate the motions of biological limbs with high fidelity. Neural interfacing technologies enable a person with amputation to control these devices with their brain and nervous system. Before long, synthetic body parts will outperform biological ones.

Our approach allows people to not only control a prosthesis with their brain, but also to feel its movements as if it were their own limb.

Against this backdrop, my colleagues and I developed a methodology to improve the connection between the biological body and a synthetic limb. Our approach, known as the agonist-antagonist myoneural interface ("AMI" for short), enables us to reflect joint movement sensations from a prosthetic limb onto the human nervous system. In other words, the AMI allows people to not only control a prosthesis with their brain, but also to feel its movements as if it were their own limb. The AMI involves a reimagining of the amputation surgery, so that the resultant residual limb is better suited to interact with a neurally-controlled prosthesis. In addition to increasing functionality, the AMI was designed with the primary goal of enabling adoption of a prosthetic limb as part of a patient's physical identity (known as "embodiment").

Early results have been remarkable. Patients with below-knee AMI amputation are better able to control an experimental prosthetic leg, compared to people who had their legs amputated in the traditional way. In addition, the AMI patients show increased evidence of embodiment. They identify with the device, and describe feeling as though it is part of them, part of self.

Where We're Going

True embodiment of robotic devices has the potential to fundamentally alter humankind's relationship with the built world. Throughout history, humans have excelled as tool builders. We innovate in ways that allow us to design and augment the world around us. However, tools for augmentation are typically external to our body identity; there is a clean line drawn between smart phone and self. As we advance our ability to integrate synthetic systems with physical identity, humanity will have the capacity to sculpt that very identity, rather than just the world in which it exists.

For this potential to be realized, we will need to let go of our reservations about surgery for augmentation. In reality, this shift has already begun. Consider the approximately 17.5 million surgical and minimally invasive cosmetic procedures performed in the United States in 2017 alone. Many of these represent patients with no demonstrated medical need, who have opted to undergo a surgical procedure for the sole purpose of synthetically enhancing their body. The ethical basis for such a procedure is built on the individual perception that the benefits of that procedure outweigh its costs.

At present, it seems absurd that amputation would ever reach this point. However, as robotic technology improves and becomes more integrated with self, the balance of cost and benefit will shift, lending a new perspective on what now seems like an unfathomable decision to electively amputate a healthy limb. When this barrier is crossed, we will collide head-on with the question of whether it is acceptable for a person to "upgrade" such an essential part of their body.

At a societal level, the potential benefits of physical augmentation are far-reaching. The world of robotic limb augmentation will be a world of experienced surgeons whose hands are perfectly steady, firefighters whose legs allow them to kick through walls, and athletes who never again have to worry about injury. It will be a world in which a teenage boy and his grandmother embark together on a four-hour sprint through the woods, for the sheer joy of it. It will be a world in which the human experience is fundamentally enriched, because our bodies, which play such a defining role in that experience, are truly malleable.

This is not to say that such societal benefits stand without potential costs. One justifiable concern is the misuse of augmentative technologies. We are all quite familiar with the proverbial supervillain whose nervous system has been fused to that of an all-powerful robot.

The world of robotic limb augmentation will be a world of experienced surgeons whose hands are perfectly steady.

In reality, misuse is likely to be both subtler and more insidious than this. As with all new technology, careful legislation will be necessary to work against those who would hijack physical augmentations for violent or oppressive purposes. It will also be important to ensure broad access to these technologies, to protect against further socioeconomic stratification. This particular issue is helped by the tendency of the cost of a technology to scale inversely with market size. It is my hope that when robotic augmentations are as ubiquitous as cell phones, the technology will serve to equalize, rather than to stratify.

In our future bodies, when we as a society decide that the benefits of augmentation outweigh the costs, it will no longer matter whether the base materials that make us up are biological or synthetic. When our AMI patients are connected to their experimental prosthesis, it is irrelevant to them that the leg is made of metal and carbon fiber; to them, it is simply their leg. After our first patient wore the experimental prosthesis for the first time, he sent me an email that provides a look at the immense possibility the future holds:

What transpired is still slowly sinking in. I keep trying to describe the sensation to people. Then this morning my daughter asked me if I felt like a cyborg. The answer was, "No, I felt like I had a foot."

A woman receives a mammogram, which can detect the presence of tumors in a patient's breast.

When a patient is diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, having surgery to remove the tumor is considered the standard of care. But what happens when a patient can’t have surgery?

Whether it’s due to high blood pressure, advanced age, heart issues, or other reasons, some breast cancer patients don’t qualify for a lumpectomy—one of the most common treatment options for early-stage breast cancer. A lumpectomy surgically removes the tumor while keeping the patient’s breast intact, while a mastectomy removes the entire breast and nearby lymph nodes.

Fortunately, a new technique called cryoablation is now available for breast cancer patients who either aren’t candidates for surgery or don’t feel comfortable undergoing a surgical procedure. With cryoablation, doctors use an ultrasound or CT scan to locate any tumors inside the patient’s breast. They then insert small, needle-like probes into the patient's breast which create an “ice ball” that surrounds the tumor and kills the cancer cells.

Cryoablation has been used for decades to treat cancers of the kidneys and liver—but only in the past few years have doctors been able to use the procedure to treat breast cancer patients. And while clinical trials have shown that cryoablation works for tumors smaller than 1.5 centimeters, a recent clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York has shown that it can work for larger tumors, too.

In this study, doctors performed cryoablation on patients whose tumors were, on average, 2.5 centimeters. The cryoablation procedure lasted for about 30 minutes, and patients were able to go home on the same day following treatment. Doctors then followed up with the patients after 16 months. In the follow-up, doctors found the recurrence rate for tumors after using cryoablation was only 10 percent.

For patients who don’t qualify for surgery, radiation and hormonal therapy is typically used to treat tumors. However, said Yolanda Brice, M.D., an interventional radiologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, “when treated with only radiation and hormonal therapy, the tumors will eventually return.” Cryotherapy, Brice said, could be a more effective way to treat cancer for patients who can’t have surgery.

“The fact that we only saw a 10 percent recurrence rate in our study is incredibly promising,” she said.

Urinary tract infections account for more than 8 million trips to the doctor each year.

Few things are more painful than a urinary tract infection (UTI). Common in men and women, these infections account for more than 8 million trips to the doctor each year and can cause an array of uncomfortable symptoms, from a burning feeling during urination to fever, vomiting, and chills. For an unlucky few, UTIs can be chronic—meaning that, despite treatment, they just keep coming back.

But new research, presented at the European Association of Urology (EAU) Congress in Paris this week, brings some hope to people who suffer from UTIs.

Clinicians from the Royal Berkshire Hospital presented the results of a long-term, nine-year clinical trial where 89 men and women who suffered from recurrent UTIs were given an oral vaccine called MV140, designed to prevent the infections. Every day for three months, the participants were given two sprays of the vaccine (flavored to taste like pineapple) and then followed over the course of nine years. Clinicians analyzed medical records and asked the study participants about symptoms to check whether any experienced UTIs or had any adverse reactions from taking the vaccine.

The results showed that across nine years, 48 of the participants (about 54%) remained completely infection-free. On average, the study participants remained infection free for 54.7 months—four and a half years.

“While we need to be pragmatic, this vaccine is a potential breakthrough in preventing UTIs and could offer a safe and effective alternative to conventional treatments,” said Gernot Bonita, Professor of Urology at the Alta Bro Medical Centre for Urology in Switzerland, who is also the EAU Chairman of Guidelines on Urological Infections.

The news comes as a relief not only for people who suffer chronic UTIs, but also to doctors who have seen an uptick in antibiotic-resistant UTIs in the past several years. Because UTIs usually require antibiotics, patients run the risk of developing a resistance to the antibiotics, making infections more difficult to treat. A preventative vaccine could mean less infections, less antibiotics, and less drug resistance overall.

“Many of our participants told us that having the vaccine restored their quality of life,” said Dr. Bob Yang, Consultant Urologist at the Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, who helped lead the research. “While we’re yet to look at the effect of this vaccine in different patient groups, this follow-up data suggests it could be a game-changer for UTI prevention if it’s offered widely, reducing the need for antibiotic treatments.”