One of the World’s Most Famous Neuroscientists Wants You to Embrace Meditation and Spirituality

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

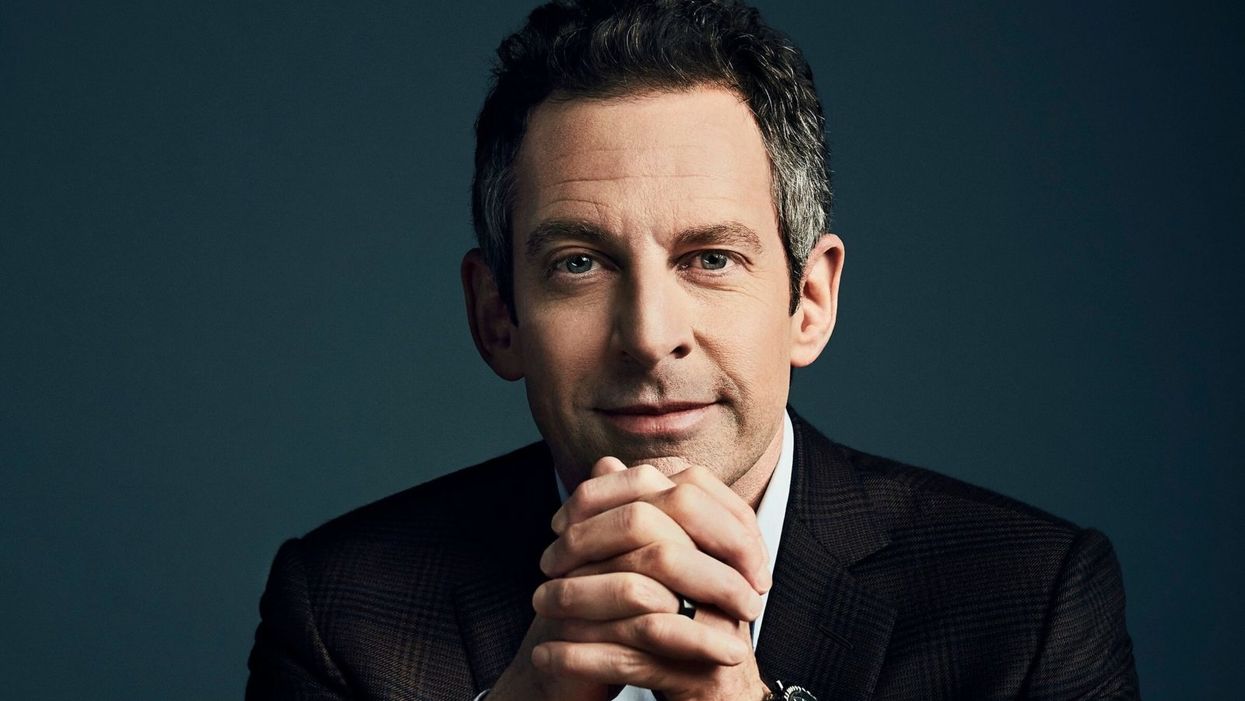

Sam Harris, the neuroscientist and bestselling author, discusses mindfulness meditation.

Neuroscientist, philosopher, and bestselling author Sam Harris is famous for many reasons, among them his vocal criticism of religion, his scientific approach to moral questions, and his willingness to tackle controversial topics on his popular podcast.

"Until you have some capacity to be mindful, you have no choice but to be lost in every next thought that arises."

He is also a passionate advocate of mindfulness meditation, having spent formative time as a young adult learning from teachers in India and Tibet before returning to the West.

Now his new app called Waking Up aims to teach the principles of meditation to anyone who is willing to slow down, turn away from everyday distractions, and pay attention to their own mind. Harris recently chatted with leapsmag about the science of mindfulness, the surprising way he discovered it, and the fundamental—but under-appreciated—reason to do it. This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed.

One of the biggest struggles that so many people face today is how to stay present in the moment. Is this the default state for human beings, or is this a more recent phenomenon brought on by our collective addiction to screens?

Sam: No, it certainly predates our technology. This is something that yogis have been talking about and struggling with for thousands of years. Just imagine you're on a beach on vacation where you vowed not to pick up your smart phone for 24 hours. You haven't looked at a screen, you're just enjoying the sound of the waves and the sunset, or trying to. What you're competing with there is this incessant white noise of discursive thinking. And that's something that follows you everywhere. It's something that people tend to only become truly sensitive to once they try to learn to meditate.

You've mentioned in one of your lessons that the more you train in mindful meditation, the more freedom you will have. What do you mean?

Sam: Well, until you have some capacity to be mindful, you have no choice but to be lost in every next thought that arises. You can't notice thought as thought, it just feels like you. So therefore, you're hostage to whatever the emotional or behavioral consequences of those thoughts are. If they're angry thoughts, you're angry. If they're desire thoughts, you're filled with desire. There is very little understanding in Western psychology around an alternative to that. And it's only by importing mindfulness into our thinking that we have begun to dimly see an alternative.

You've said that even if there were no demonstrable health benefits, it would still be valuable to meditate. Why?

Sam: Yeah, people are putting a lot of weight on the demonstrated health and efficiency benefits of mindfulness. I don't doubt that they exist, I think some of the research attesting to them is pretty thin, but it just may in fact be the case that meditation improves your immune system, and staves off dementia, or the thinning of the cortex as we age and many other benefits.

"What was Jesus talking about? Well, he certainly seemed to be talking about a state of mind that I first discovered on MDMA."

[But] it trivializes the real power of the practice. The power of the practice is to discover something fundamental about the nature of consciousness that can liberate you from psychological suffering in each moment that you can be aware of it. And that's a fairly esoteric goal and concern, it's an ancient one. It is something more than a narrow focus on physical health or even the ordinary expectations of well-being.

Yet many scientists in the West and intellectuals, like Richard Dawkins, are skeptical of it. Would you support a double-blind placebo-controlled study of meditation or does that miss the deeper point?

Sam: No, I see value in studying it any way we can. It's a little hard to pick a control condition that really makes sense. But yeah, that's research that I'm actually collaborating in now. There's a team just beginning a study of my app and we're having to pick a control condition. You can't do a true double-blind placebo control because meditation is not a pill, it's a practice. You know what you're being told to do. And if you're being told that you're in the control condition, you might be told to just keep a journal, say, of everything that happened to you yesterday.

One way to look at it is just to take people who haven't done any significant practice and to have them start and compare them to themselves over time using each person as his own control. But there are limitations with that as well. So, it's a little hard to study, but it's certainly not impossible.

And again, the purpose of meditation is not merely to reduce stress or to improve a person's health. And there are certain aspects to it which don't in any linear way reduce stress. You can have stressful experiences as you begin to learn to be mindful. You become more aware of your own neuroses certainly in the beginning, and you become more aware of your capacity to be petty and deceptive and self-deceptive. There are unflattering things to be realized about the character of your own mind. And the question is, "Is there a benefit ultimately to realizing those things?" I think there clearly is.

I'm curious about your background. You left Stanford to practice meditation after an experience with the drug MDMA. How did that lead you to meditation?

Sam: The experience there was that I had a feeling -- what I would consider unconditional love -- for the first time. Whether I ever had the concept of unconditional love in my head at that point, I don't know, I was 18 and not at all religious. But it was an experience that certainly made sense of the kind of language you find in many spiritual traditions, not just what it's like to be fully actualized by those, by, let's say, Christian values. Like, what was Jesus talking about? Well, he certainly seemed to be talking about a state of mind that I first discovered on MDMA. So that led me to religious literature, spiritual or new age literature, and Eastern philosophy.

Looking to make sense of this and put into a larger context that wasn't just synonymous with taking drugs, it was a sketching a path of practice and growth that could lead further across this landscape of mind, which I just had no idea existed. I basically thought you have whatever mind you have, and the prospect of having a radically different experience of consciousness, that would just be a fool's errand, and anyone who claimed to have such an experience would probably be lying.

As you probably know, there's a resurgence of research in psychedelics now, which again I also fully support, and I've had many useful experiences since that first one, on LSD and psilocybin. I don't tend to take those drugs now; it's been many years since I've done anything significant in that area, but the utility is that they work for everyone, more or less, which is to say that they prove beyond any doubt to everyone that it's possible to have a very different experience of consciousness moment to moment. Now, you can have scary experiences on some of these drugs, and I don't recommend them for everybody, but the one thing you can't have is the experience of boredom. [chuckle]

Very true. Going back to your experiences, you've done silent meditation for 18 hours a day with monks abroad. Do you think that kind of immersive commitment is an ideal goal, or is there a point where too much meditation is counter-productive to a full life?

Sam: I think all of those possibilities are true, depending on the person. There are people who can't figure out how to live a satisfying life in the world, and they retreat as a way of trying to untie the knot of their unhappiness directly through practice.

But the flip side is also true, that in order to really learn this skill deeply, most people need some kind of full immersion experience, at least at some point, to break through to a level of familiarity with it that would be very hard to get for most people practicing for 10 minutes a day, or an hour a day. But ultimately, I think it is a matter of practicing for short periods, frequently, more than it's a matter of long hours in one's daily life. If you could practice for one minute, 100 times a day, that would be an extraordinarily positive way to punctuate your habitual distraction. And I think probably better than 100 minutes all in one go first thing in the morning.

"It's amazing to me to walk into a classroom where you see 15 or 20 six-year-olds sitting in silence for 10 or 15 minutes."

What's your daily meditation practice like today? How does it fit into your routine?

Sam: It's super variable. There are days where I don't find any time to practice formally, there are days where it's very brief, and there are days where I'll set aside a half hour. I have young kids who I don't feel like leaving to go on retreat just yet, but I'm sure retreat will be a part of my future as well. It's definitely useful to just drop everything and give yourself permission to not think about anything for a certain period. And you're left with this extraordinarily vivid confrontation with your default state, which is your thoughts are incessantly appearing and capturing your attention and deluding you.

Every time you're lost in thought, you're very likely telling yourself a story for the 15th time that you don't even have the decency to find boring, right? Just imagine what it would sound like if you could broadcast your thoughts on a loud speaker, it would be mortifying. These are desperately boring, repetitive rehearsals of past conversations and anxieties about the future and meaningless judgments and observations. And in each moment that we don't notice a thought as a thought, we are deluded about what has happened. It's created this feeling of self that is a misconstrual of what consciousness is actually like, and it's created in most cases a kind of emotional emergency, which is our lives and all of the things we're worrying about. But our worry adds absolutely nothing to our capacity to deal with the problems when they actually arise.

Right. You mentioned you're a parent of a young kid, and so am I. Is there anything we as parents can do to encourage a mindfulness habit when our kids are young?

Sam: Actually, we just added meditations for kids in the app. My wife, Annaka, teaches meditation to kids as young as five in school. And they can absolutely learn to be mindful, even at that age. And it's amazing to me to walk into a classroom where you see 15 or 20 six-year-olds sitting in silence for 10 or 15 minutes, it's just amazing. And that's not what happens on the first day, but after five or six classes that is what happens. For a six-year-old to become aware of their emotional life in a clear way and to recognize that he was sad, or angry…that's a kind of super power. And it becomes a basis of any further capacity to regulate emotion and behavior.

It can be something that they're explicitly taught early and it can be something that they get modeled by us. They can know that we practice. You can just sit with your kid when your kid is playing. Just a few minutes goes a long way. You model this behavior and punctuate your own distraction for a short period of time, and it can be incredibly positive.

Lastly, a bonus question that is definitely tongue-in-cheek. Who would win in a fight, you or Ben Affleck?

Sam: That's funny. That question was almost resolved in the green room after that encounter. That was an unpleasant meeting…I spend some amount of time training in the martial arts. This is one area where knowledge does count for a lot, but I don't think we'll have to resolve that uncertainty any time soon. We're both getting old.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

A woman receives a mammogram, which can detect the presence of tumors in a patient's breast.

When a patient is diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, having surgery to remove the tumor is considered the standard of care. But what happens when a patient can’t have surgery?

Whether it’s due to high blood pressure, advanced age, heart issues, or other reasons, some breast cancer patients don’t qualify for a lumpectomy—one of the most common treatment options for early-stage breast cancer. A lumpectomy surgically removes the tumor while keeping the patient’s breast intact, while a mastectomy removes the entire breast and nearby lymph nodes.

Fortunately, a new technique called cryoablation is now available for breast cancer patients who either aren’t candidates for surgery or don’t feel comfortable undergoing a surgical procedure. With cryoablation, doctors use an ultrasound or CT scan to locate any tumors inside the patient’s breast. They then insert small, needle-like probes into the patient's breast which create an “ice ball” that surrounds the tumor and kills the cancer cells.

Cryoablation has been used for decades to treat cancers of the kidneys and liver—but only in the past few years have doctors been able to use the procedure to treat breast cancer patients. And while clinical trials have shown that cryoablation works for tumors smaller than 1.5 centimeters, a recent clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York has shown that it can work for larger tumors, too.

In this study, doctors performed cryoablation on patients whose tumors were, on average, 2.5 centimeters. The cryoablation procedure lasted for about 30 minutes, and patients were able to go home on the same day following treatment. Doctors then followed up with the patients after 16 months. In the follow-up, doctors found the recurrence rate for tumors after using cryoablation was only 10 percent.

For patients who don’t qualify for surgery, radiation and hormonal therapy is typically used to treat tumors. However, said Yolanda Brice, M.D., an interventional radiologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, “when treated with only radiation and hormonal therapy, the tumors will eventually return.” Cryotherapy, Brice said, could be a more effective way to treat cancer for patients who can’t have surgery.

“The fact that we only saw a 10 percent recurrence rate in our study is incredibly promising,” she said.

Urinary tract infections account for more than 8 million trips to the doctor each year.

Few things are more painful than a urinary tract infection (UTI). Common in men and women, these infections account for more than 8 million trips to the doctor each year and can cause an array of uncomfortable symptoms, from a burning feeling during urination to fever, vomiting, and chills. For an unlucky few, UTIs can be chronic—meaning that, despite treatment, they just keep coming back.

But new research, presented at the European Association of Urology (EAU) Congress in Paris this week, brings some hope to people who suffer from UTIs.

Clinicians from the Royal Berkshire Hospital presented the results of a long-term, nine-year clinical trial where 89 men and women who suffered from recurrent UTIs were given an oral vaccine called MV140, designed to prevent the infections. Every day for three months, the participants were given two sprays of the vaccine (flavored to taste like pineapple) and then followed over the course of nine years. Clinicians analyzed medical records and asked the study participants about symptoms to check whether any experienced UTIs or had any adverse reactions from taking the vaccine.

The results showed that across nine years, 48 of the participants (about 54%) remained completely infection-free. On average, the study participants remained infection free for 54.7 months—four and a half years.

“While we need to be pragmatic, this vaccine is a potential breakthrough in preventing UTIs and could offer a safe and effective alternative to conventional treatments,” said Gernot Bonita, Professor of Urology at the Alta Bro Medical Centre for Urology in Switzerland, who is also the EAU Chairman of Guidelines on Urological Infections.

The news comes as a relief not only for people who suffer chronic UTIs, but also to doctors who have seen an uptick in antibiotic-resistant UTIs in the past several years. Because UTIs usually require antibiotics, patients run the risk of developing a resistance to the antibiotics, making infections more difficult to treat. A preventative vaccine could mean less infections, less antibiotics, and less drug resistance overall.

“Many of our participants told us that having the vaccine restored their quality of life,” said Dr. Bob Yang, Consultant Urologist at the Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, who helped lead the research. “While we’re yet to look at the effect of this vaccine in different patient groups, this follow-up data suggests it could be a game-changer for UTI prevention if it’s offered widely, reducing the need for antibiotic treatments.”