Our devices are changing us

Tech-related injuries are becoming more common as many people depend on - and often develop addictions for - smart phones and computers.

In the 1990s, a mysterious virus spread throughout the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Artificial Intelligence Lab—or that’s what the scientists who worked there thought. More of them rubbed their aching forearms and massaged their cricked necks as new computers were introduced to the AI Lab on a floor-by-floor basis. They realized their musculoskeletal issues coincided with the arrival of these new computers—some of which were mounted high up on lab benches in awkward positions—and the hours spent typing on them.

Today, these injuries have become more common in a society awash with smart devices, sleek computers, and other gadgets. And we don’t just get hurt from typing on desktop computers; we’re massaging our sore wrists from hours of texting and Facetiming on phones, especially as they get bigger in size.

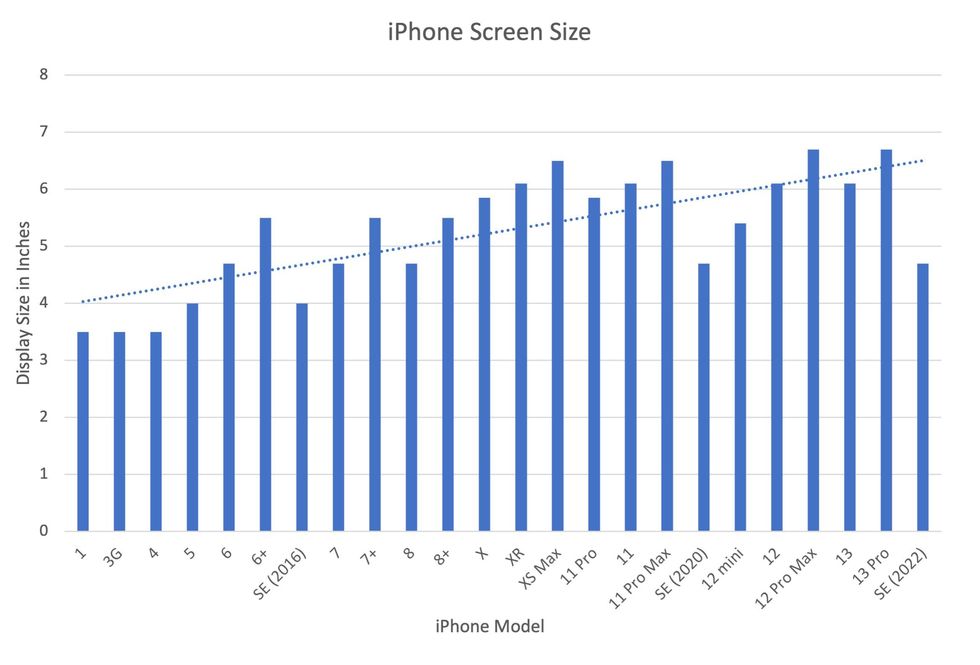

In 2007, the first iPhone measured 3.5-inches diagonally, a measurement known as the display size. That’s been nearly doubled by the newest iPhone 13 Pro, which has a 6.7-inch display. Other phones, too, like the Google Pixel 6 and the Samsung Galaxy S22, have bigger screens than their predecessors. Physical therapists and orthopedic surgeons have had to come up with names for a variety of new conditions: selfie elbow, tech neck, texting thumb. Orthopedic surgeon Sonya Sloan says she sees selfie elbow in younger kids and in women more often than men. She hears complaints related to technology once or twice a day.

The addictive quality of smartphones and social media means that people spend more time on their devices, which exacerbates injuries. According to Statista, 68 percent of those surveyed spent over three hours a day on their phone, and almost half spent five to six hours a day. Another report showed that people dedicate a third of their day to checking their phones, while the Media Effects Research Laboratory at Pennsylvania State University has found that bigger screens, ideal for entertainment purposes, immerse their users more than smaller screens. Oversized screens also provide easier navigation and more space for those with bigger hands or trouble seeing.

But others with conditions like arthritis can benefit from smaller phones. In March of 2016, Apple released the iPhone SE with a display size of 4.7 inches—an inch smaller than the iPhone 7, released that September. Apple has since come out with two more versions of the diminutive iPhone SE, one in 2020 and another in 2022.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance science journalist, has the Google Pixel 6. She was drawn to the phone because Google marketed the Pixel 6’s camera as better at capturing different skin tones. But this phone boasts one of the largest display sizes on the market: 6.4 inches.

Senapathy was diagnosed with carpal and cubital tunnel syndromes in 2017 and fibromyalgia in 2019. She has had to create a curated ergonomic workplace setup, otherwise her wrists and hands get weak and tingly, and she’s had to adjust how she holds her phone to prevent pain flares.

Recently, Senapathy underwent an electromyography, or an EMG, in which doctors insert electrodes into muscles to measure their electrical activity. The electrical response of the muscles tells doctors whether the nerve cells and muscles are successfully communicating. Depending on her results, steroid shots and even surgery might be required. Senapathy wants to stick with her Pixel 6, but the pain she’s experiencing may push her to buy a smaller phone. Unfortunately, options for these modestly sized phones are more limited.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers like Senapathy to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable for creating addictive devices that lead to musculoskeletal injury?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance journalist, bought the Google Pixel 6 because of its high-quality camera, but she’s had to adjust how she holds the oversized phone to prevent pain flares.

Kavin Senapathy

A one-size-fits-all mentality for smartphones will continue to lead to injuries because every user has different wants and needs. S. Shyam Sundar, the founder of Penn State’s lab on media effects and a communications professor, says the needs for mobility and portability conflict with the desire for greater visibility. “The best thing a company can do is offer different sizes,” he says.

Joanna Bryson, an AI ethics expert and professor at The Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, Germany, echoed these sentiments. “A lot of the lack of choice we see comes from the fact that the markets have consolidated so much,” she says. “We want to make sure there’s sufficient diversity [of products].”

Consumers can still maintain some control despite the ubiquity of tech. Sloan, the orthopedic surgeon, has to pester her son to change his body positioning when using his tablet. Our heads get heavier as they bend forward: at rest, they weigh 12 pounds, but bent 60 degrees, they weigh 60. “I have to tell him, ‘Raise your head, son!’” she says. It’s important, Sloan explains, to consider that growth and development will affect ligaments and bones in the neck, potentially making kids even more vulnerable to injuries from misusing gadgets. She recommends that parents limit their kids’ tech time to alleviate strain. She also suggested that tech companies implement a timer to remind us to change our body positioning.

In 2017, Nan-Wei Gong, a former contractor for Google, founded Figur8, which uses wearable trackers to measure muscle function and joint movement. It’s like physical therapy with biofeedback. “Each unique injury has a different biomarker,” says Gong. “With Figur8, you are comparing yourself to yourself.” This allows an individual to self-monitor for wear and tear and strengthen an injury in a way that’s efficient and designed for their body. Gong noticed that the work-from-home model during the COVID-19 pandemic created a new set of ergonomic problems that resulted in injuries. Figur8 provides real-time data for these injuries because “behavioral change requires feedback.”

Gong worked on a project called Jacquard while at Google. Textile experts weave conductive thread into their fabric, and the result is a patch of the fabric—like the cuff of a Levi’s jacket—that responds to commands on your smartphone. One swipe can call your partner or check the weather. It was designed with cyclists in mind who can’t easily check their phones, and it’s part of a growing movement in the tech industry to deliver creative, hands-free design. Gong thinks that engineers at large corporations like Google have accessibility in mind; it’s part of what drives their decisions for new products.

Display sizes of iPhones have become larger over time.

Sourced from Screenrant https://screenrant.com/iphone-apple-release-chronological-order-smartphone/ and Apple Tech Specs: https://www.apple.com/iphone-se/specs/

Back in Germany, Joanna Bryson reminds us that products like smartphones should adhere to best practices. These rules may be especially important for phones and other products with AI that are addictive. Disclosure, accountability, and regulation are important for AI, she says. “The correct balance will keep changing. But we have responsibilities and obligations to each other.” She was on an AI Ethics Council at Google, but the committee was disbanded after only one week due to issues with one of their members.

Bryson was upset about the Council’s dissolution but has faith that other regulatory bodies will prevail. OECD.AI, and international nonprofit, has drafted policies to regulate AI, which countries can sign and implement. “As of July 2021, 46 governments have adhered to the AI principles,” their website reads.

Sundar, the media effects professor, also directs Penn State’s Center for Socially Responsible AI. He says that inclusivity is a crucial aspect of social responsibility and how devices using AI are designed. “We have to go beyond first designing technologies and then making them accessible,” he says. “Instead, we should be considering the issues potentially faced by all different kinds of users before even designing them.”

A woman receives a mammogram, which can detect the presence of tumors in a patient's breast.

When a patient is diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, having surgery to remove the tumor is considered the standard of care. But what happens when a patient can’t have surgery?

Whether it’s due to high blood pressure, advanced age, heart issues, or other reasons, some breast cancer patients don’t qualify for a lumpectomy—one of the most common treatment options for early-stage breast cancer. A lumpectomy surgically removes the tumor while keeping the patient’s breast intact, while a mastectomy removes the entire breast and nearby lymph nodes.

Fortunately, a new technique called cryoablation is now available for breast cancer patients who either aren’t candidates for surgery or don’t feel comfortable undergoing a surgical procedure. With cryoablation, doctors use an ultrasound or CT scan to locate any tumors inside the patient’s breast. They then insert small, needle-like probes into the patient's breast which create an “ice ball” that surrounds the tumor and kills the cancer cells.

Cryoablation has been used for decades to treat cancers of the kidneys and liver—but only in the past few years have doctors been able to use the procedure to treat breast cancer patients. And while clinical trials have shown that cryoablation works for tumors smaller than 1.5 centimeters, a recent clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York has shown that it can work for larger tumors, too.

In this study, doctors performed cryoablation on patients whose tumors were, on average, 2.5 centimeters. The cryoablation procedure lasted for about 30 minutes, and patients were able to go home on the same day following treatment. Doctors then followed up with the patients after 16 months. In the follow-up, doctors found the recurrence rate for tumors after using cryoablation was only 10 percent.

For patients who don’t qualify for surgery, radiation and hormonal therapy is typically used to treat tumors. However, said Yolanda Brice, M.D., an interventional radiologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, “when treated with only radiation and hormonal therapy, the tumors will eventually return.” Cryotherapy, Brice said, could be a more effective way to treat cancer for patients who can’t have surgery.

“The fact that we only saw a 10 percent recurrence rate in our study is incredibly promising,” she said.

Urinary tract infections account for more than 8 million trips to the doctor each year.

Few things are more painful than a urinary tract infection (UTI). Common in men and women, these infections account for more than 8 million trips to the doctor each year and can cause an array of uncomfortable symptoms, from a burning feeling during urination to fever, vomiting, and chills. For an unlucky few, UTIs can be chronic—meaning that, despite treatment, they just keep coming back.

But new research, presented at the European Association of Urology (EAU) Congress in Paris this week, brings some hope to people who suffer from UTIs.

Clinicians from the Royal Berkshire Hospital presented the results of a long-term, nine-year clinical trial where 89 men and women who suffered from recurrent UTIs were given an oral vaccine called MV140, designed to prevent the infections. Every day for three months, the participants were given two sprays of the vaccine (flavored to taste like pineapple) and then followed over the course of nine years. Clinicians analyzed medical records and asked the study participants about symptoms to check whether any experienced UTIs or had any adverse reactions from taking the vaccine.

The results showed that across nine years, 48 of the participants (about 54%) remained completely infection-free. On average, the study participants remained infection free for 54.7 months—four and a half years.

“While we need to be pragmatic, this vaccine is a potential breakthrough in preventing UTIs and could offer a safe and effective alternative to conventional treatments,” said Gernot Bonita, Professor of Urology at the Alta Bro Medical Centre for Urology in Switzerland, who is also the EAU Chairman of Guidelines on Urological Infections.

The news comes as a relief not only for people who suffer chronic UTIs, but also to doctors who have seen an uptick in antibiotic-resistant UTIs in the past several years. Because UTIs usually require antibiotics, patients run the risk of developing a resistance to the antibiotics, making infections more difficult to treat. A preventative vaccine could mean less infections, less antibiotics, and less drug resistance overall.

“Many of our participants told us that having the vaccine restored their quality of life,” said Dr. Bob Yang, Consultant Urologist at the Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, who helped lead the research. “While we’re yet to look at the effect of this vaccine in different patient groups, this follow-up data suggests it could be a game-changer for UTI prevention if it’s offered widely, reducing the need for antibiotic treatments.”

The rise of remote work is a win-win for people with disabilities and employers